How an M6.5 Earthquake Led to a Historic Avalanche Cycle in the Sawtooths

Words by SMG co-owner Chris Lundy, Photos by guide Tanner Haskins

The Experience

On March 31st, Sara and I were up at the Williams Peak Hut shoveling it out from nearly 2 feet of new snow. The yurts have been shut down for several weeks due to the COVID-19 pandemic—which means there’s no one up there to keep them from getting buried with snow. We had just finished the digging and were relaxing in the warm hut. Then our world was rocked.

At 5:52 pm, everything started to shake, rumble, and sway. We ran outside and the first thing I saw is an image that will stick with me forever. The snow-laden trees were swinging side to side, and the new snow they had been holding was exploding everywhere. Almost immediately, we heard a different sort of rumbling—the kind that comes from large avalanches. Keep in mind that all of this happened in a matter of seconds, and my brain was still processing what was happening. My first thought was that a massive avalanche was about to hit the hut—an irrational thought since the yurts are in a safe location. Sara, having grown up in Idaho and experienced the 1983 Borah earthquake, knew exactly what was going on. I am still struck by how vulnerable you feel when the Earth stops standing still, especially in the mountains where gravity wants to pull things downhill.

The earthquake stopped, and then eventually so did the rumbling of avalanches. It took much longer for the adrenaline to die down. No sooner had we begun taking stock of what happened than our phones start exploding with texts from neighbors, friends, and family, checking in with us and each other. Was everyone ok? Is there any damage? Are people’s houses in Stanley still standing? Eventually, the subject of the messages shifted from “is everyone ok” to “what just happened?”

The Earthquake

Here’s what we learned, some of it just after the earthquake and other details emerged later. The earthquake was a magnitude 6.5 that stuck just 20 miles NW of Stanley and the mountain range that Sawtooth Mountain Guides calls home. It was the second-largest earthquake on record in Idaho, behind the 1983 M6.9 Borah event that raised the state’s highest peak several feet. Interestingly, it occurred in the Shake Creek drainage just north of Cape Horn and Banner Summit. Is it a coincidence that the drainage is named Shake Creek? Maybe not, since historical records recall the nearby Seafoam earthquakes in 1944 and 1945 (M6.1 and M6.0). For anyone who wants to learn more about this event, be sure to check out College of Southern Idaho Geology Professor (and part-time SMG guide) Shawn Willsey‘s informative video.

While an earthquake of this magnitude is not common for Idaho, something else makes this a truly rare and historic event: it struck at the tail-end of one of the winter’s largest storms when the avalanche danger was rated HIGH. Based on the sound of avalanches that we heard during and right after the earthquake, and the fact that Stanley residents could even hear the rumbling in town, it was clear that the earthquake had produced a massive avalanche cycle. But just how extensive wouldn’t be evident until the next day.

The Aftermath

While being at our house in Stanley when the quake struck would have been unforgettable, experiencing it high in the Sawtooths where we could hear snow crashing down around us made it an indescribably powerful experience. Once we confirmed things were all good on the homefront, we couldn’t resist the opportunity to spend the night and be around when the storm cleared in the morning.

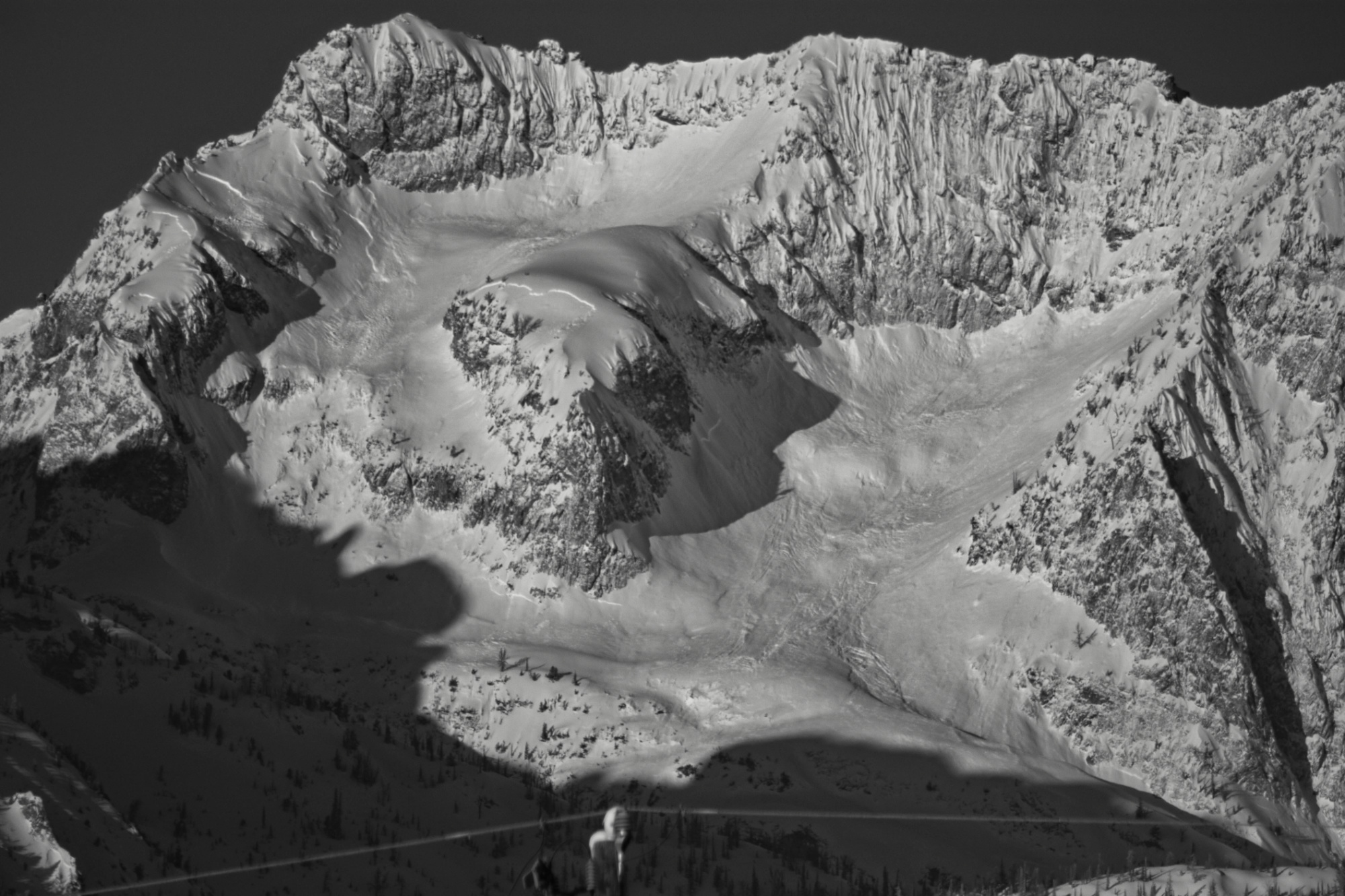

April 1st dawned clear and cold, and at first light, we saw our first avalanches in Tortilla and Marshall Slides. We also saw that the steep slope threatening the approach to Skier’s Summit had already slid—which made us feel okay about heading for the popular high point. Cresting the shoulder onto the Jerry Garcia ski run offered us our first glimpse of Profile Basin and Thompson Peak, and the extent of the avalanche activity hit home. The snow had slid from nearly every steep slope—and there’s a lot of steep slopes in the Sawtooths—in some way, shape, or form. Slabs had fractured, powder had sluffed, and hanging snowfields had come unglued from vertical rock. The aprons below the steeper terrain were covered with piles upon piles of avalanche debris.

Another interesting phenomenon we saw that day was widespread cracking and spider-webbing of slopes that had some pitch, but weren’t steep enough to avalanche. It was as if the snowy mantle covering the Sawtooths had shattered. Many of these cracks went clear through the snowpack to the ground.

When we got home from the Williams Peak Hut, we saw photos from those that experienced the aftermath on a larger, range-wide scale. SMG guide and photographer Tanner Haskins drove along the front range of the Sawtooths, snapping photos that revealed the sheer extent of avalanche activity that resulted from the earthquake (see photo gallery below). There were literally hundreds of miles of slab avalanche fracture lines. Snow avalanches were not all that happened—a number of major rock faces and features had broken off. The Arrowhead—a rock climb and visually-striking feature at the head of the Hellroaring drainage—is no more. How did the Sawtooth’s other famous rock climbs fare? Time will tell.

The Timing

With most of the country (and certainly central Idaho) shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many folks have been yearning for news other than the usual infection counts and dire predictions. It seems that this earthquake provided a much-needed distraction from our current situation, and was a reminder that even while dealing with something as globally-impactful as COVID-19, there are still larger forces at play.