In the beginning: Snow Science

When I first started teaching avalanche courses 20 years ago, snow science was in something of a golden age and we thought it was going to save lives. I spent a lot of time with students digging snowpits, looking at snow crystals, and performing various tests. Little did we know that we weren’t giving our students the complete picture.

In 2000, snow researcher Ian McCammon published a study finding that the level of avalanche training did not reduce the amount of avalanche hazard backcountry travelers exposed themselves too. In fact, those with a basic level of avalanche training may even expose themselves to more hazard. In this paper and in future work, McCammon uncovered compelling evidence that in the majority of avalanche accidents, there were several “obvious clues” present that indicated unstable conditions.These conclusions were alarming to say the least. Why wasn’t avalanche education making people safer in the backcountry? If the conditions were obviously unstable, why were people still exposing themselves to steep terrain?

A new era: How to make a decision

Over time it became clear that people get caught in avalanches not because they misunderstand the avalanche hazard, but rather because they made poor decisions. Especially when faced with a complex environment, incomplete information, and the intense emotional stimulus of powder riding, rational decision making flies out the window. Recognizing this, many avalanche courses, especially those following an American Institute for Avalanche Research and Education (AIARE) curriculum, began focusing less on evaluating avalanche hazard and more on providing students a systematic and repeatable decision making process. The key components of this process are heading out the door armed with a plan, gathering information to determine if avalanche conditions are as expected, and if so, enacting the plan in a manner that exposes the fewest people.

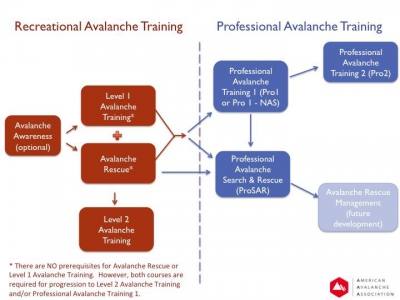

The next frontier: the Pro/Rec Split

As we got a better handle on how to effectively manage avalanche risk, fine tuning the message further proved difficult – especially at more advanced levels of training. The average Level 2 course is a mix of recreational skiers as well as current and aspiring professionals such as guides and ski patrollers, and many of us found this course challenging to teach well. Further, the perception among recreational skiers that have completed a Level 1 is that the Level 2 is more advanced than they need and as a result, over 80% of L1 graduates never take a L2. However, a L1 is truly an intro level class and most backcountry riders would benefit from additional education.

Beginning this winter, and fully in place by the 2017-18 winter, the American Avalanche Association (AAA) Education Committee (chaired by SMG’s founder Kirk Bachman) is spearheading a split in U.S. avalanche education, separating the course progression into recreational and professional tracks. What this means for recreational backcountry skiers is a more coherent, streamlined, and relevant course progression, with an important objective of reducing the attrition rate between L1 and L2 courses. Recreational folks that were previously intimidated by the L2 curriculum will now find it to be a natural extension of the L1.

This coming winter, we at Sawtooth Mountain Guides plan to start aligning our courses, especially the Level 2, with the new AAA guidelines for recreational avalanche courses. For the 2017-18 winter, AIARE will have a fully updated curriculum for both the L1 and L2 courses which will usher in the next era of avalanche education.

Chris Lundy

SMG Co-Owner, AIARE Course Leader, AAA Certified Instructor